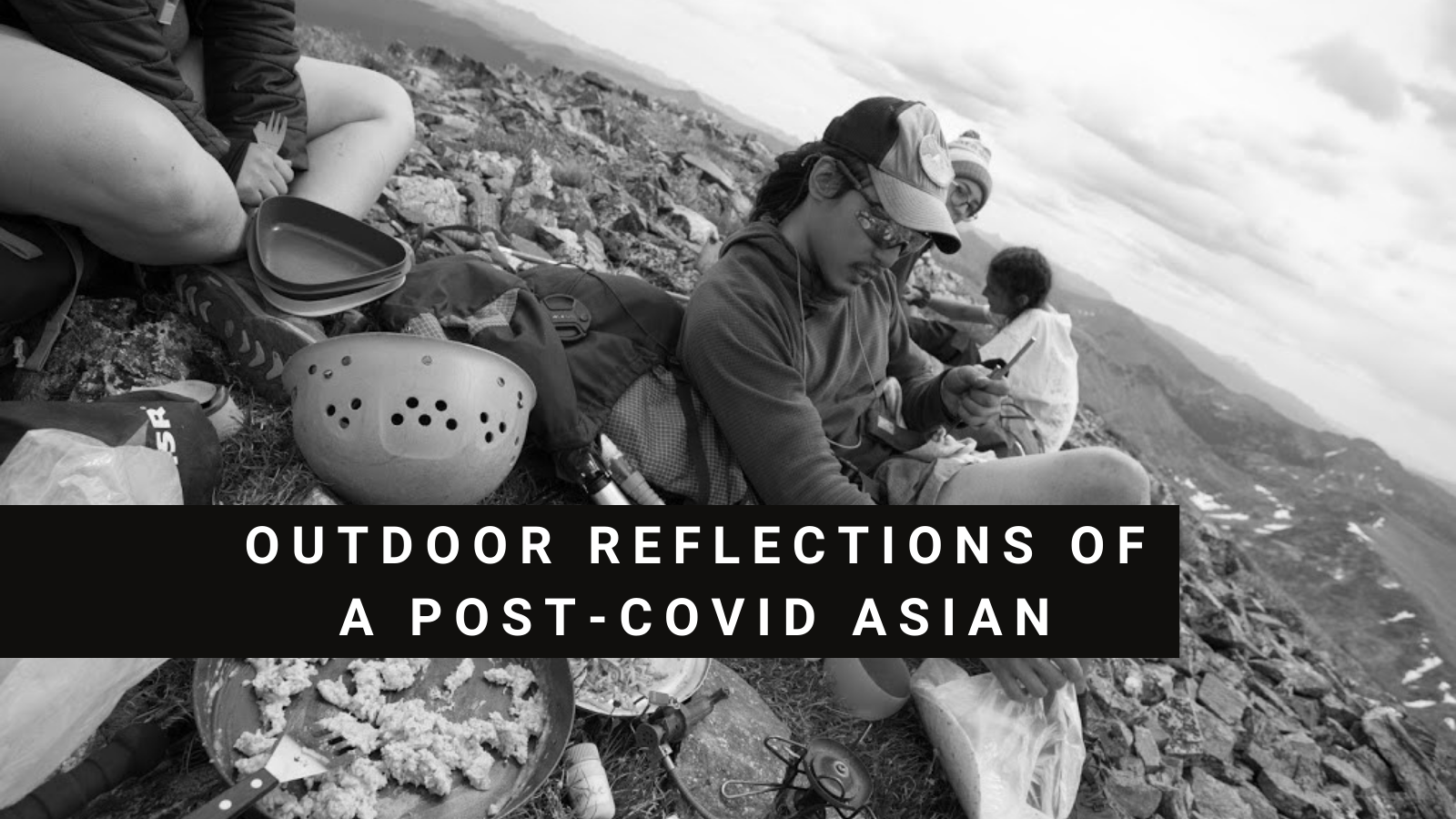

Jessica - a BIPOC Outdoor Mental Health Story

Content warning: This article mentions bipolar disorder and passive suicidal thinking.

“Coming from a background where my parents didn’t really believe in mental illness meant I didn’t get the help I needed until I sought it myself,” said Jessica, an Asian American skydiver from California’s Central Coast. After being misdiagnosed with depression as a child, she eventually received a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder and ADHD in college. Prior to that, she struggled with symptoms for years to include passive suicidal thinking. “I honestly thought that was normal for the majority of my life,” Jessica recalled. After she began to experience difficulty getting out of bed, she finally opened up to friends who encouraged her to seek help.

“Having bipolar means being sentenced to a lifetime of mood stabilizers,” Jessica reflected. “It’s taken me a really long time to come to terms with it. A lot of the therapy I’ve been going through recently is understanding that these diagnoses aren’t necessarily life sentences but another feature of what makes me a unique individual.”

“Skydiving for me has been incredibly therapeutic. It really helps re-center me and brings me to a place where I feel stable and where I feel like I belong.”

For many Asian Americans like Jessica, getting help means navigating a stunning lack of diversity in the mental health field. The mental health specialists she's worked with so far have been overwhelmingly white and male. “Having my treatment administered by people who don’t understand my cultural identity is difficult,” Jessica explained. “Whenever I talk about the trauma I experienced as a kid due to my immigrant parents or because of my family’s cultural norms, there has never been real understanding.”

Jessica also relies on a strong support system of people who can help provide insight into her illness—something she struggles with during episodes—as well as love and understanding. That doesn’t erase the challenges she faces as a member of a culture that heavily stigmatizes mental health. “It made me want to take everything on by myself and hide it away because I was incredibly ashamed of it,” Jessica admitted. “I wish that my culture would open up to the idea of mental illness and address it in a more forward and helpful way.” Her experience is a familiar one for many people of color who struggle with a system that doesn’t recognize our culture and a culture that doesn’t recognize our illness.

“I’m learning to feel less ashamed as I slowly embrace the diagnosis I carry.”

These days Jessica’s mental health journey includes medication, therapy and spending a lot of time outdoors practicing yoga, rock climbing and backpacking at California state parks. She began skydiving a little over a year ago and has accumulated over 300 solo jumps. “Skydiving for me has been incredibly therapeutic,” said Jessica. “It really helps re-center me and brings me to a place where I feel stable and where I feel like I belong.” The outdoors isn’t a replacement for medication or therapy. However, for many people living with mental illness, it offers a chance to feel grounded in the present moment.

“I’m learning to feel less ashamed as I slowly embrace the diagnosis I carry,” said Jessica, who recently befriended another person with bipolar on a skydiving trip. “It turns out that it’s easier to navigate the outdoors with someone else that you can align yourself with.”

Outdoor communities can be a part of making the outdoors safer and more inclusive for people of color who are living with mental illness. Here’s how.

Q&A

Inclusive language matters, stigmatizing language hurts

I think it’s important to form spaces for people with mental illness who are seeking the outdoors as a form of healing. One way to do so is to be more mindful of the inappropriate jokes about mental health. Hardly a week goes by without my hearing, “Oh my god, they’re so bipolar” or “I’m so bipolar.” It’s tough to interrupt someone and say, “Hey, let’s be mindful of what we’re saying.” You never want to be the person who can’t take a joke, especially when I’m not comfortable with letting people know about my diagnosis. It gets touchy.

GET HELP TODAY

The National Suicide Prevention Hotline: 800-273-8255

Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio: 888-628-9454

Deaf & Hard of Hearing: 800-799-4889

The Trevor Project Suicide Prevention Hotline for LGBTQ+ Youth: 866-488-7386

Becoming a mountain biker meant occupying a one-size-fits-all identity. It was difficult. If you are brown or different in any way from the white, male, able bodied athletes promoted by major brands, your task is to assimilate.