Melanin, I Love You

I can’t recall the exact moment when it occurred to me that my brown skin was seen by others as a burden, as ugly, as tasteless, as lower class. I can, however, recall snippets of childhood memories that eventually led to that realization. I remember my relatives yelling at me to stop playing in the sun; I remember my aunt telling my cousin that her skin was dark and ugly—casually, as if discussing something as mundane as the weather; and of course, I remember the ever-present skin whitening products that stocked the aisles at the drugstore.

As long as I can remember, the topic of skin color was ubiquitous. There was no defining moment because it was always there, ever-present, and always informing the choices I made.

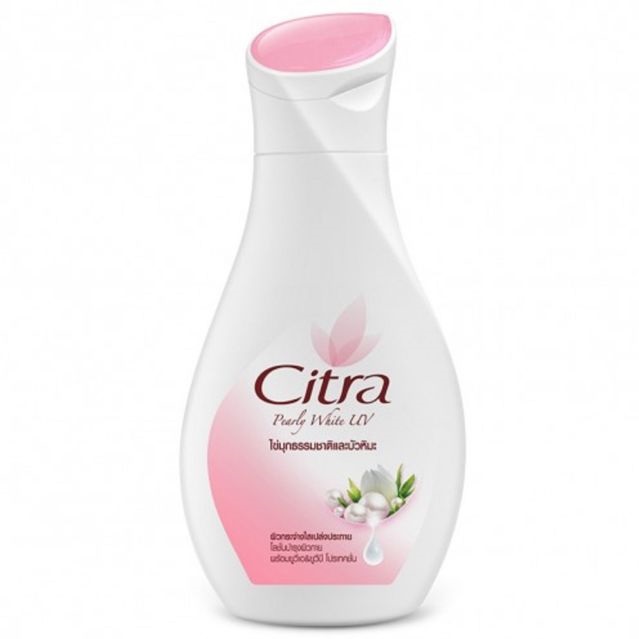

I grew up in Thailand where skin color has the power to differentiate one’s class, one’s opportunities, one’s education level, and one’s beauty, among a plethora of other things. As such, preserving one’s skin was always the goal. When I entered middle school, I, as many other young girls do, became interested in using cosmetics. My friends and I would go to the local drugstore and sample the lip gloss that was supposed to plump up our lips, the eyeshadow that would supposedly make our eyes pop, and the concealer that would brighten and lighten our skin. My exposure to the cosmetics industry in Thailand was the first time in which I understood the normalization of such a concept; of how, from birth, we were conditioned to believe that lighter skin was more desirable, and if we were darker, were taught a self-hatred for our own skin.

I grew up attending an international school in Thailand which meant that I had many friends who were white, Asian or biracial. For the most part, they eagerly participated in outdoor sports. I, on the other hand, worried incessantly about exposing my already brown skin to the sun. Even though I am half Thai, half white, I have darker skin. Instead of soccer or rugby, I tried out for the indoor volleyball team. During beach trips to the beautiful islands in the Gulf of Thailand, I felt incredibly anxious about all the time we were spending in the sun. After all, each minute spent in the sun made me darker. I’d watch as my friends with lighter skin basked in the sunlight, happily absorbing its rays. Getting darker was fun for them, almost like a game. They’d gleefully show off their tan lines and compare them to one another as if it were some sort of accomplishment. Contrarily, my tan lines haunted me.

I attended college at UC Santa Barbara, a sleepy little beach town in Goleta, California. I was excited and nervous about the opportunity to lounge on the beach and swim in the cool Pacific Ocean between classes. I was thrilled that this was where I would spend the next four years of my life, but anxiety over sun exposure still followed me. How would I stay out of the sun? How would I avoid getting dark?

Gradually, I found myself placing less and less importance on “preserving my skin.” I continued wearing sunscreen because protecting one’s skin is important, but I began caring less about the actual color of my skin. I found myself feeling comfortable enough to go hiking, play on the beach with my friends for hours at a time, bike to and from classes in the California heat, and just be in the sun without worrying. Over time, I didn’t care about how dark the sun made my skin; instead, I came to love it. I no longer monitored my skin’s lightness or darkness but began to appreciate it and love myself for it. My skin was just as dark as it should be, and no one could tell me any differently.

Now, while pursuing my PhD in sociology at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, I am studying the impact of colorism, racism, and globalization in Southeast Asia. My research examines the different opportunities that lighter skinned Thais have traditionally enjoyed in comparison to their darker skinned counterparts. I know, however, that this problem is not unique to Thailand. It isn’t even unique to southeast Asian countries like Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, but is a global phenomenon. This subject resonates deeply with my own experience as a darker skinned Thai. Additionally, I recognize the importance of dismantling a system that devalues darker skinned folks in terms of attractiveness, self-worth, employment opportunities, educational opportunities, relationship opportunities and more.

I recently took my annual trip home to Thailand to visit family and friends. After visiting my father in Bangkok, where I mostly grew up, I took a week-long trip up north to visit my mother and my Thai extended family in Chiang Rai. My family lives in a remote village atop a hill near the border with Laos. Over the past ten years, nothing in the village has changed with the exception of the main dirt road which is now paved. They speak Isaan (a Thai dialect), live well below the national poverty level, and are mostly rice, rubber, and corn farmers. They are darker skinned people and, due to their occupational status, are constantly exposed to the sun. Since I currently live in Hawai’i and spend most of my time outside hiking, swimming in the ocean, biking and climbing outdoors, I am also very dark.

One of my uncles, who is very dark himself, commented on how dark my skin was multiple times during my visit. He expressed his disappointment with how dark I had become--especially because my skin had been so much lighter when I was younger. Finally, he laughed as he told me I was the darkest white person he knew. Hearing this ten or even just four years ago would have caused a completely different reaction. I would’ve felt disgusted by myself. I would’ve longed to be lighter, or even whiter. I now understand that, just like the infrastructure, absolutely nothing else had changed in the village in the past ten years. The only thing different was me: my mindset, my ideas, and my self-worth. I couldn’t be upset with my uncle who had been taught the exact same thing I was but who had never had the opportunity to fall in love with his own brown skin, and himself.

As a brown person, I feel so deeply grateful to love my skin and no longer feel threatened by the sun. I feel privileged to have the ability to explore the outdoors, and to create experiences and memories with loved ones. I feel privileged to appreciate mother nature and all she has to offer without fear. I hope that we can address the underlying systemic issues which contribute to the colorism within each of our communities and vow to play our role in being part of a more positive public discourse.

To end, I’d like to share something I wrote when I was 20 years old (I am now 22):

An Ode to Melanin

Dear Melanin,

I remember the first day I noticed you, the first time I felt you

Like a drop of blood in water, you slowly took over, and I let you

You blew through my body like a tsunami, there was no time to prepare, no time for me to speak.

Your touch was magic; golden and shimmering.

It was then that I understood. I understood your presence.

You consumed me.

Melanin, I hate you.

I want to rip all traces of you from my skin. I want nothing to do with you.

At the age of seven, my mother told me to stay out of the sun,

Otherwise I would be darker. She meant uglier.

At the age of thirteen, a white man asked if I was a nanny,

I shook my head no and watched as his face scrunched up in confusion.

At the age of fourteen, my boyfriend told me he preferred when I stayed out of the sun,

When I was lighter.

At the age of seventeen, I held my tongue as people told me I spoke English very well,

Considering.

Melanin, I’m sorry.

I blamed you.

I never defended you, I was ashamed of you.

Melanin, I love you.

I love you the way you make me feel,

I am ever-changing, glowing, resplendent, and wild,

I am iridescent; the sun shines and I am anew.

At the age of eighteen, I could feel you again.

At the age of nineteen, I learned how to stop hiding. I learned how to stop apologizing

For the color of my skin.

At the age of twenty, I dance in the sunlight as its rays wrap their arms around my skin,

They pull me in closer. I feel warm. I feel at home.

My body finally feels like home.

Melanin, I love you.

Photo credit: Jessica Champagne

Do you love the outdoors? Do you have a lot of outdoorsy friends? Are most of them White? Well, you might relate to the following experiences. Eugene Pak lays out ten things he wishes his outdoorsy White friends knew about him..