Lions and Tigers and Black Folk, Oh My! Why Black People Should Take Up Space in the Outdoors

Photo of the author on Nüümu and Newe Segobia (Western Shoshone) land. Photo courtesy of Joshua Walker

"Stuff white people like."

"Stuff black people just don't do."

Those are a few things you hear when discussing black people's involvement in outdoor recreation.

I had a different experience. I grew up on a farm. We had cows, I milked them. We also had hogs and chickens. Some mornings I would go out to the barn to see if the chickens laid eggs and that was breakfast. I drove tractors, planted and tended to fields and gardens, and rode dirt bikes and four wheelers in the woods. I climbed trees, chased bugs and lizards, and used to lie in the grass under a nice shady tree to escape long days of work in the fields during the summer.

At any given time, you could find me under my tree with my encyclopedias and nature library books. I loved identifying plants and insects in the woods directly behind my house. You could also find me in those same trees doing homework or reading a book in my brothers deer stand. That was my childhood, and I loved it.

Growing up, because I was young and impressionable, I also aligned myself to the belief that there were things in life that were inherently just for white people. That long list included camping, hiking, skiing, most water sports, skydiving, etc. And while I personally always wanted to try some of the outdoor activities I considered off-limits, I did not feel like I would fit in for two reasons: I was black and most of the kids that did those things also didn't make it a habit of hanging out with black kids.

Photo of the author on Nüümu and Newe Segobia (Western Shoshone) land. Photo courtesy of Joshua Walker

I should mention that I was raised in South Carolina. That means the segregation seen in those activities also involved racism—the main reason my parents didn't want to encourage my involvement. I, however, resisted and found myself at my first (mostly white) sleep away summer camp, Camp Wildwood, where I slept in cabins, waded in water with snakes, completed my first night hike, and participated in relay races. That camp furthered my passion for nature and the outdoors and honestly contributed to who I am today.

Unfortunately, everyone does not have that same experience. Even my siblings, who were also farm kids, don't enjoy the same activities that I do. While I understand the phrase “different strokes for different folks,” this issue, in my opinion, is much more deeply rooted than a mere matter of taste. I believe it to be the byproduct of systemic racism.

If there are any white folks reading this who are tired of we black folks playing the race card, I urge you to continue reading. Something about this topic initially intrigued you and maybe, just maybe, I have something to teach you. My purpose for writing this article is to erase the stigma of being an African-American who is afraid of camping, or hiking, or swimming, and to change the narrative that white folks have about what black people do or don't do.

Photo by Josh Carter on Unsplash

Facts are facts even though high school U.S. history classes typically have a funny relationship with the truth. By that, I mean large tracts of American history that are embarrassing, shameful, and despicable often get remixed or removed from the narrative. Especially growing up in the South, it takes a lot of digging to one day realize that the war between the states was about slavery, not states rights.

Uncovering historical truth requires that matters of education be taken into one’s own hands. To begin to understand this topic we need to go back in time a bit. Even before we were brought to the colonies as slaves, white men encoded racial hatred and white supremacy into American jurisprudence—thus allowing for the sale and purchase of black people. The same legal code decided that we were three-fifths of a person while also punishing us for learning to read or write.

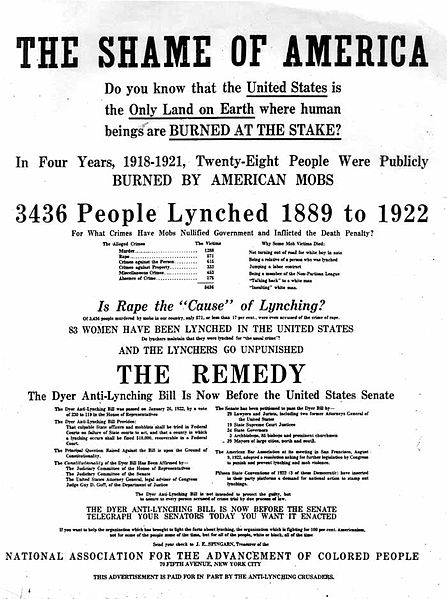

Later on, after slavery ended, new laws were added to run blacks out of political office, restrict our right to vote, obstruct black home ownership, and legally establish racial segregation alongside new forms of slavery like share-cropping and the prison system. And where the law was insufficient, informal measures existed. The Klu Klux Klan, sundown towns, cross burnings, bombings, intimidation, harassment, murder and massacres of black townships were all tools used to dehumanize, terrorize and devalue blacks while reinforcing white supremacy.

Double-speak on race is nothing new. Getty Images

Racial hatred of black people is a thoroughly American tradition and it persists alongside the belief in the racial inferiority of black Americans. Although nowadays, it gets coded as people we don’t want in our neighborhood, students we don’t want in our schools, new hires we don’t want on our executive track, missing kids we don’t actually care about and urban hikers we don’t want on our trails. If the law doesn't respect black folks, why should anyone else?

Camping was actually established as a way for the wealthy and elite to venture out into the wild. However, when cars began to be mass produced, camping became more accessible. When black folks started to partake in those activities, the National Park Service responded by creating segregated parks, or segregating campsites within existing parks. There were literally NATIONAL PARKS THAT WERE SEGREGATED. White men did not even want us outside. We were free but still policed everywhere we went.

David Isom breaks the color line at a whites only swimming pool in Florida, June 1958. White officials responded by—you guessed it!—closing the pool. Getty Images

That’s why knowing our history is important. Here’s another example: “Black children ages 5 to 19 drown in swimming pools at a rate more than five times that of white children.” Those are numbers that get tossed around in countless articles puzzling over why those black people just don’t how to swim.

Here’s what many of those studies don’t talk about: segregated beaches and the thousands of “Whites only” swimming pools that opened in urban areas during the 1920s and 30s. When faced with integration in the 1960s, cities across the U.S. chose to defund their public pools rather than allow black bodies into a formerly all white space. The era of the free city public pool was over; white swimmers and white families decamped for whites only suburbs and whites only private pools.

Photo of the author on Nüümu and Newe Segobia (Western Shoshone) land. Photo courtesy of Joshua Walker

Unfortunately, not much has changed. Black and brown people are constantly policed outdoors by white people and are made to feel that “regardless of income and postal address, as black bodies moving around in white claimed spaces, they are constantly at risk of being seen as dangerous intruders.” Cue, white people calling the police on black people in the outdoors for daring to push their son in a stroller at a local park, pick up trash in their own yard, sell water, mow lawns in the neighborhood, use the pool at their condo, play golf, or barbecue in a local park. That was just 2018. Of course, when asked directly, the response is always that “Nature doesn’t see color” or “everyone is welcome in the outdoors.” Actions seem to indicate otherwise.

Of course, that does not apply to all white people but it applies to a lot and we have seen that much more lately, thanks to social media. Thankfully, the National Park Service has been trying to implement changes to encourage minority participation in nature. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for a single PR campaign to overcome centuries of systemic racism that have led to fear, wariness and discomfort.

Venturing to national parks, even in the absence of discriminatory policies, is very difficult for MOST black people today. Let us consider where our national parks are located. If you divide the U.S in half longitudinally, most national parks are located between the mid-west and the west coast. Most African Americans are not. Many of us still live in the Southeast. Planning a trip to visit one of America’s crown jewels becomes incredibly expensive. Aint gonna happen level of expensive. It would require flights, hotels, car rentals, equipment rentals, park passes, and paid time off to really experience all that the parks have to offer. The alternative is living close by in an all white or mostly white mountain town.

Now lets get back to that little thing called slavery that many folks would rather not talk about. I had a really great conversation with a black therapist who specializes in generational trauma which essentially means that people can inherit their parent’s trauma. When talking to her, I could not help but think that this generational trauma thing could potentially go back more than just one or two generations. When we think about why people say "black people don't go camping" we need to really consider why that is.

For a long time, the woods were a scary place for people with my skin color. Bad things happened in the woods if you were a runaway slave. Bad things happened in the rural south if you were a black man driving through the wrong town after dark. All of these events have scarred the collective imagination of the wilderness for a lot of black people. The same applies for water activities. Our ancestors arrived by the sea; many drowned, or were thrown overboard, or even jumped to escape bondage. Whether that trauma has been passed down or compounded by other factors, learning to swim is something that just does not happen in black households unlike with other races.

My parents, born in the 1940s, did not grow up around integrated pools, so they didn't learn to swim; and because of that they couldn't teach us how to swim. Inner city black kids don’t have access to public pools and neither did their parents nor their grandparents. I personally didn't learn to swim until my junior year of college. I was 20-years-old.

Despite America’s legacy of racism and white supremacy, we are a resilient community. Head southeast and you’ll find that most black folks’ connection to the outdoors is through hunting and fishing—two activities closely tied to conservation and stewardship of the land. We are outdoors and we are building connections with nature on our own terms. But even if there is generational trauma—even if and when we are afraid, or hesitant or wary about recreating in “white claimed” spaces—that’s okay too.

I feel safe in the woods. I feel comforted by the trees. I feel energized by the soil and rocks. I feel awakened by the breeze. I feel invigorated and inspired by the rain. I am fascinated by storms. Nature is terrifying but only because of the unlimited capability it possesses but I do not fear nature. And my hope, above everything else, is that black and brown people start inhabiting this space more. If we are expected to sing and believe “This Land Is Your Land” or the National Anthem—if we are expected to say the Pledge of Allegiance, and if we are expected to fully cherish and respect OUR country, then WE need to start fully inhabiting it.

Sometimes you just have to go for it! Getty Images

Joshua Walker loves spending time in the outdoors. This born and raised South Carolinian can be found enjoying nature’s splendor in California and wherever nature may be found. To connect, check out joshyoutrippin.com or find him on Instagram at @joshyoutrippin. Just hold the sweet tea please.

As knowledge of the outdoors tends to be handed down generationally, this broken chain has denied today’s black youth the tools they need to be able to tackle the outdoors with any degree of confidence […] we have effectively become an urbanised people.