An African American Climber's Guide to "Being the Only One"

Justin Forrest Parks owes his sense of exploration and curiosity to his parents who raised him to defy expectations and find his own path. (Photo credit: Michael Estrada, Brown Environmentalist)

Meet Forrest Parks; at 26 years-old they are a sport climber, a Deuter ambassador, an Outdoor Research grassroots athlete and a Diversify Outdoors coalition member. They began climbing at age 16, became a world traveler at 18 and found both passion and purpose in making the Outdoors a more inclusive community—first in Chicago where they co-founded Sending In Color and now at the National Outdoor Leadership School in Lander, Wyoming where they serve as the Diversity and Inclusion Manager.

But before they were any of those things, Forrest was a Black kid growing up on the south side of Chicago on Mascouten ancestral land. Both of their parents were born and raised in Chicago, one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. Forrest’s mom grew up in Englewood and their dad was raised in Calumet Heights, a Black middle class enclave that integrated in the 1960s.

Forrest’s grandparents were part of the Second Migration of Black southerners who left the Jim Crow South after WWII in search of better prospects in Chicago; tripling the city’s Black population to over 800,000 in the period between 1940 and 1960. Then as in now, Chicago was a deeply segregated city. However, it was also a beacon of hope for the hundreds of thousands of Black southerners who found steady jobs in manufacturing plants and helped shape a renaissance of Black culture, literature and music.

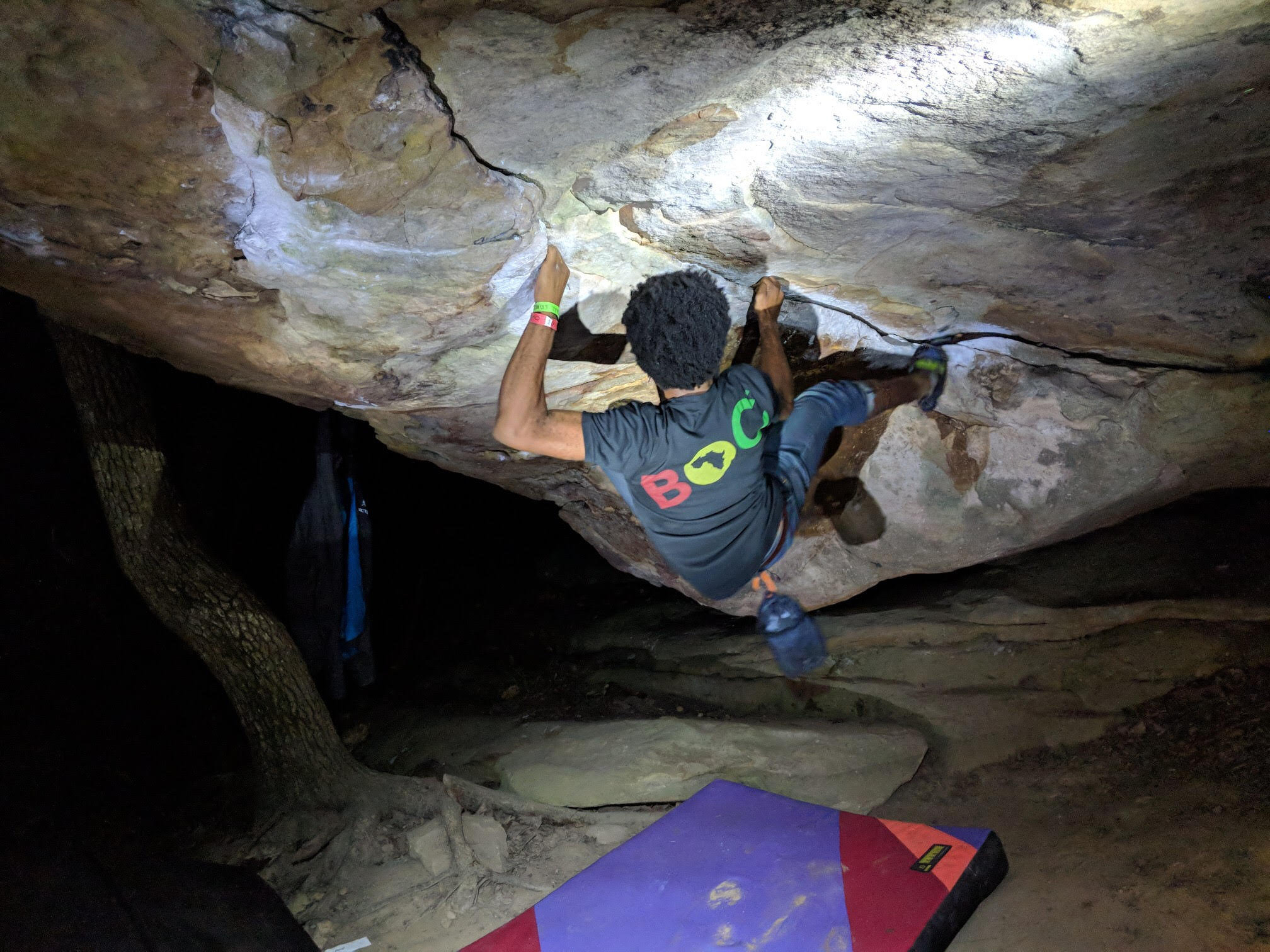

After almost ten years of “being the only one” Justin has found a community of ethnically diverse climbers through Sending In Color along with NYC based Brothers of Climbing which co-hosts the annual event Color the Crag in Steele, Alabama (Photo credit: Christine Joy Antonio).

The post-war era was also an ugly period in Chicago’s history. Black Chicagoans faced employment and housing discrimination. Redlining, discriminatory federal loan practices and housing covenants prohibited Black homeownership in White neighborhoods. African-Americans were segregated on Chicago’s South Side in majority Black neighborhoods where public services were defunded or neglected. Meanwhile a decline in manufacturing jobs further devastated Black working class families.

Black Chicagoans faced incredible odds including overcrowded schools, a spike in crime and gang violence, and very little economic investment—a stark contrast to Chicago’s downtown and northwest commercial districts where the vast majority of jobs and investment capital are located. Although today Chicago is one of the most prosperous cities in the U.S., the legacy of legal and de facto segregation is visible in the divide between rich and poor, Black and White, North and South. That’s one way to look at it. For Forresr, the South Side was simply home.

A photo of Justin’s paternal grandparents on their wedding day.

Forrest grew up in an apartment on the border of Roseland and Pullman that was filled with music. Their mom sang and played the guitar. She defied expectations as the only Black woman to be president of the folk singer John Denver fan club at the time. She was also a carpenter and one of the few women in her union in Chicago. Their dad was equally musically gifted; he played the guitar, bass drums and the keyboard. He also worked as a HVAC specialist and computer analyst.

Forrest’s parents met in a music store in downtown Chicago where their mother was playing guitar. According to family lore, Forrest’s paternal grandfather was a strict, former military man with a low tolerance for music. In spite of this, the two fell in love and were married. The little family grew: Forresr, who was born in 1992, grew up playing guitar, piano, banjo and mandolin. Eight years later, the Parks added another boy—a younger brother named Austin who is a percussionist at the Merit School of Music and jams with renown jazz musicians in the city.

The Parks lived close to 103rd St. and Western Ave, a dividing line that separated White and Black. Forrest attended elementary school in tony Morgan Park. When it became too much of a financial strain, their parents transferred them to a private Christian school 20 minutes away in Oak Lawn, Illinois. Forrest spent their days in an almost all-white private school then went home to an all-Black neighborhood where local schools were under-resourced and pockmarked by violence. Their parents worked hard to ensure that both of their children would have options. But by the time they enrolled at Chicago Christian High School in Palos Heights, Forrest was “starting to feel like I didn’t fit in there.”

Justin’s parents both grew up on the South Side of Chicago; his mom was raised in Englewood; his dad grew up in Calumet Heights.

Part of their restlessness was grappling with “being a Black kid in this all white school in these all white neighborhoods.” Figuring out how to thrive in spaces where you’re ‘the only one’ was not that straightforward; they wanted out. Forrest’s parents gave them the option to homeschool or attend a local school on the South Side; Forrest chose homeschooling. It turned out to be a mistake; “I hated it—turns out I learn better with people around.” The upside was spending a lot of time getting to know the city—all of it. They began hanging out at libraries and museums as well as at prestigious public schools in downtown Chicago. The end of their private school education was actually a beginning: for the first time in Forrest’s life their education became limited only by their curiosity and appetite for new experiences.

In addition to homeschooling Forrest’s parents exposed them to nature. Like many Black Chicagoans, Forrest also has roots down South. When they were younger, that meant road-trips to Georgia to attend family reunions, weddings, funerals. Growing up, they spent a lot of time wandering around on a great uncle’s land where there were horses, cows, and hound dogs. While Forrest’s first outdoor experiences came through family; their first introduction to rock climbing came through church.

Justin’s parents both share a passion for music (Photo credit: Justin Forrest Parks).

As a teenager, Forrest traveled to South Africa for a mission trip with their local church. Looking back, they remarked that “I have an issue with voluntourism which I now recognize that was, but I really appreciated the opportunity.” During the trip, the group flew up to Jozi and stayed for a couple hours on a game range close to Mt. Everest (the other one). One day, one of the group leaders invited Forrest to accompany them to the local crag to check out some sport climbing routes. He pointed out the bolts, or the shiny things in the rocks. That’s what stoked Forrest’s curiosity.

Back in Chicago, 16-year-old Forrest joined friends on a rock climbing trip up to Devil’s Lake in Baraboo, Wisconsin where they learned top roping. Afterwards, they got connected to a gym where they learned to lead climb. They were pretty fearless indoors which allowed them to progress quickly “while taking lots of [whippers]”—semi-controlled falls that require careful coordination between the belayer and climber to avoid serious injury. Climbing was exciting; it meant new places, new people and new experiences. It was also a familiar foray into spaces where very few people looked like them; climbing gyms in Chicago are clustered in White neighborhoods on the north and west sides of the highly segregated city.

After mastering the basics at indoor gyms, Forrest traveled as far as the Red River Gorge, a popular sport climbing destination eight hours away in Slade, KY—“pulling on large jugs with dynamic moves on long overhanging routes that went on forever.” They fell in love with “sport [climbing] because it allows me to use my body to solve a mental challenge to go with the flow and become entranced by the movement.” They also found “lots of community and mentors in my gym, so the progression to the outdoors felt pretty organic and natural.”

Forrest also developed a serious case of wanderlust. They got into couch surfing which their mom fervently opposed—at least initially. Forrest explained that, “a lot of my life has been relentlessly pursuing an activity until I wear my parents down. It’s a strategy.” It’s also a strategy they came by honestly. Their father used the same relentless passion for music to wear down Forrest’s grandfather.

After attending high school for one year and homeschooling for two years, Forrest obtained their GED. They enrolled in Columbia College in Chicago and began studying cinematography, but not for long. Next, they set their sights on travel. Forrest joined AmeriCorps for two years and traveled all around the US, working in Mississippi, Alabama, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Louisiana.

At the time, their family had strong objections. Forrest explained, “although my mother is a very cool cultured woman, camping is just not her thing. That was actually a struggle between us.” Their family had typical Black parent concerns. There was Forrest’s happiness to consider, but also their safety “as an African American…traveling on my own or being out in the wilderness. Now she’s really supportive but it’s been a journey. She can see the happiness and joy I get from travel and from being outside.”

Next, Forrest joined the Montana Conservation Corps and moved to Missoula where they took up residence in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, a 1.3 million tract of protected land across Idaho and Montana located in the Bitterroot Mountain Range. Their mother was not thrilled; she channeled her discontent into a robust letter writing campaign. Meanwhile, Forrest adapted quickly to backcountry living. Motorized objects were prohibited in the Wilderness so the crew used classic crosscut saws to clear fallen trees from trails in the backcountry for hunters and the U.S. Forest Service. The job lasted for six months. Immediately afterwards, they moved to Australia.

Australia was the culmination of a six year friendship with an Australian pen pal. Forrest couchsurfed with musicians in Melbourne and explored the city. Their friend flew in and then the pair were off to Sydney. Afterwards they stayed at a homestead in the Blue Mountains, before visiting her hometown in Byron Bay. From there they parted ways; Forrest moved into a rainforest just outside of Mullumbimby. They stayed with her uncle in an A frame home while helping out with greenhouse projects. Eventually, Forrest came back to Chicago for love but that didn’t work out.

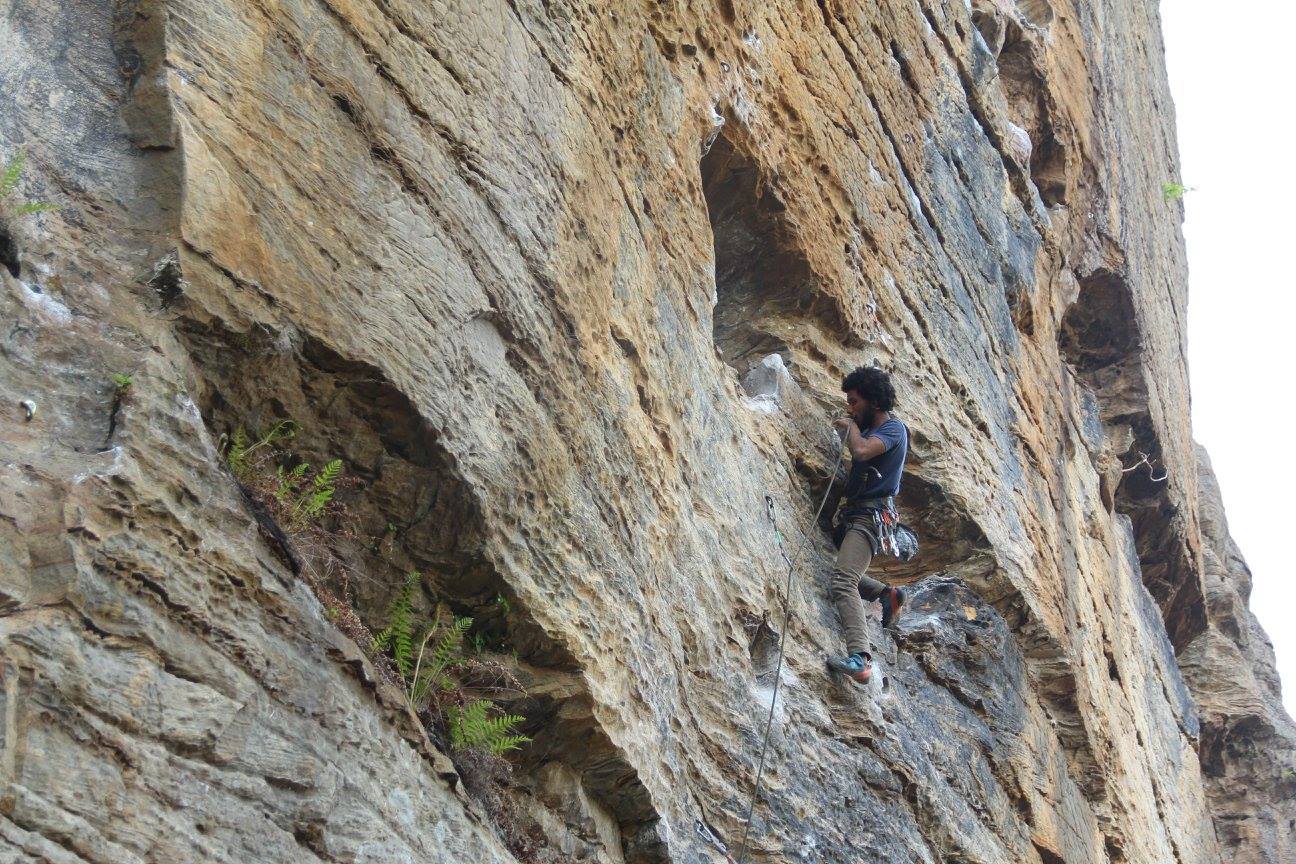

Photo of Justin sport climbing in the Red River Gorge, Slade, Kentucky (Photo credit: Justin Forrest Parks)

Their love of climbing still took them away from home. There were sport climbing trips to the Red River Gorge, traditional climbing trips to Devils Lake, WI and bouldering in Jackson Falls, IL. Forrest loved the journey to remote climbing spots just as much as the climb itself. They are comfortable climbing 5.12a-c and consistently sends 5.11c projects, however, they’re always up for new experiences. That includes bouldering, where Forrest had their first injury and met most of their climbing friends. They fell in love with “the quick intense challenges and how the goal is not always to go up but sometimes sideways or just to be upside down.”

Back in Chicago, Forrest’s parents struggled to come to terms with their high-risk hobbies. They explained, “first, my mother didn’t want me riding motorcycles. Then when I told her I was flying to Peru to climb a mountain she forgot about the motorcycle.” Forrest traveled next to Huaraz, Peru in La Cordillera Blanca to complete crevasse rescue and glacier travel training. Their goal at this point was to become a mountain guide. This was the culmination of years of reading and dreaming about mountaineering. Forrest knew they would have to leave the country—or at least the lower 48–in order to complete high altitude training. They chose the School for International Expedition Training because the founder, Josh Buckner, provided guide focused instruction with an emphasis on technical competence and professionalism.

It was a grueling course that culminated in a guided expedition up Tocllaraju, a 19,790 ft peak in the Peruvian Andes. The name is derived from the Quechua words tuqlla (trap) and rahu (snow). Three of the clients started feeling altitude sickness and had to descend back down the mountain. The rest continued their ascent only to turn back fifty feet from the summit because conditions were deteriorating. Forrest was 23 years old.

After Peru, they returned to Chicago in 2016 and started working at Chicago Cares as their corporate volunteer programs logistics assistant and volunteer engagement coordinator. They began dreaming of building a climbing gym on the Chicago’s South Side to increase awareness of the sport and access to Chicago’s African American communities. They also co-founded Sending In Color, a monthly meet-up for climbers of color in Chicago along with co-founder Pilar Amado.

Forrest’s goal with Sending In Color and their new position as the Diversity & Inclusion Manager for the National Outdoor Leadership School is to “help create equitable spaces and experiences that engage, promote, and amplify everyone in our community.” For Forrest, that means asking hard questions and encouraging organizational growth. They believe in taking up space and feeling a sense of ownership even if you are “the only one.” They are also determined to influence others not to “make decisions or opinions based off of misinformation or stereotypes. Before you make broad statements about an activity or a group of people it’s important to understand it first. We need to have conversations. People love to vilify each other and to feel right but it’s important to learn from one another.”

As a Black climber, mountaineer and international traveler, they are used to dealing with the assumptions of others, and the consequences of stereotypes. After all, “society connotes Black with negative headlines, with bad things. But as a Black AMAB* in Chicago I can’t just know the South Side.” They have grown accustomed to existing in two different communities: predominantly White climbing spaces and predominantly Black spaces where they grew up. Forrest doesn’t offer any easy answers. As they learned as a child, it’s incredibly difficult to feel ownership in places where you are the “only one.” It can be difficult to feel welcome or included. In the mean time, they are grateful for their ancestors and a family legacy of curiosity and exploration—and of perseverance.

*AMAB means assigned male at birth.

After all, their grandparents left the Jim Crow South and traveled over 800 miles to start a new life in a city. Leaving home took courage. Perhaps they were also motivated by hope and dreams of a better future other than the racial prejudice that awaited them. Forrest’s paternal grandfather fought in the Korean War only to return home to a country which continued to view him as a second class citizen. Forrest’s parents pursued their love of music and raised their kids with the same desire to learn and experience the world on their own terms so that “every new experience, every hobby is an opportunity to figure out how the world works.” Now, their goal is to help others do the same.

As a kid, I loved roller skating and occasionally ventured onto the ice rink at the mall during the winter. Back then, fear wasn’t even a consideration. If I fell, I simply brushed it off and kept going. So why does stepping out of our comfort zones feel so much harder as adults?