Oreo: Growing Up Black in Post-Racial America

Rowing six seat during my junior year of high school.

I grew up in a Black family in the 90s and early aughts. Both of my parents were military officers, but by the time I was born, my mother left the Army to work part-time and raise four kids. We lived in safe, leafy, mostly white suburbs outside of military bases. We spent summers riding bikes, playing outside with friends and soaking up air conditioning at the local library. It was a middle-class upbringing. We weren’t poor and we weren’t rich.

Despite living in predominantly white neighborhoods my childhood wasn’t necessarily whitewashed. My parents filled our house with Black dolls, books and pamphlets on African-American scientists, inventors, educators, and activists. When I was younger, there weren’t many children’s books with Black protagonists. The ones that were available focused primarily on historical accounts of slavery and the Civil Rights movement; so that was what we read.

I grew up learning about Ida B. Wells, Mary McLeod Bethune and Sojourner Truth along with George Washington Carver, Charles Drew and Benjamin Banneker. While I loved learning about African-American history, I also envied white children with the latest Barbies, Polly Pocket compacts and complete sets of Nancy Drew & Hardy Boy Super Mysteries. At home, we had my mom’s collection of Ernest J. Gaines & Toni Morrison hardcovers. I also had my own private stash of $0.25 Herman Wouk novels and overdue sci-fi library books, set in the distant future where Black people were noticeably absent.

Our childhood felt typical for Black kids in the 90s. We had a lot of television shows to choose from: Martin, Family Matters, Moesha, Living Single, Fresh Prince, etc. My favorite was A Different World, because it featured Black ROTC cadets, something I could relate to. We played outside every day and came home when the streetlights came on; Saturday all-day house cleanings started with loud gospel music; my mom stashed sewing supplies in biscuit tins; special occasions meant bumped ends, singed ears and a lot of tears; we went to church, got spanked for disobedience; and drove to grandma’s house on holidays for fried chicken, collared greens, homemade biscuits and sweet tea. We were four bespectacled, skinny, quiet Black kids.

So what does internalized racism have to do with my Norman Rockwell childhood? Well, it seeped into our family, same as any other Black family during that period. Despite being raised to be a well-adjusted, confident, Black kid, I wanted to be White.

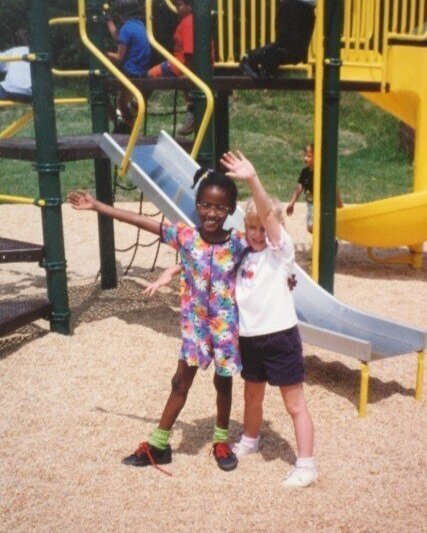

Family portrait with a plus one! Not sure whose kid this is, lol. The families we socialized with were mostly other white military families who were connected to my Dad in some way. He attended high school in Germany, college at the U.S. Military Academy and then served 20 years in the Army so his upbringing was very much like mine.

Good Hair vs. Bad Hair

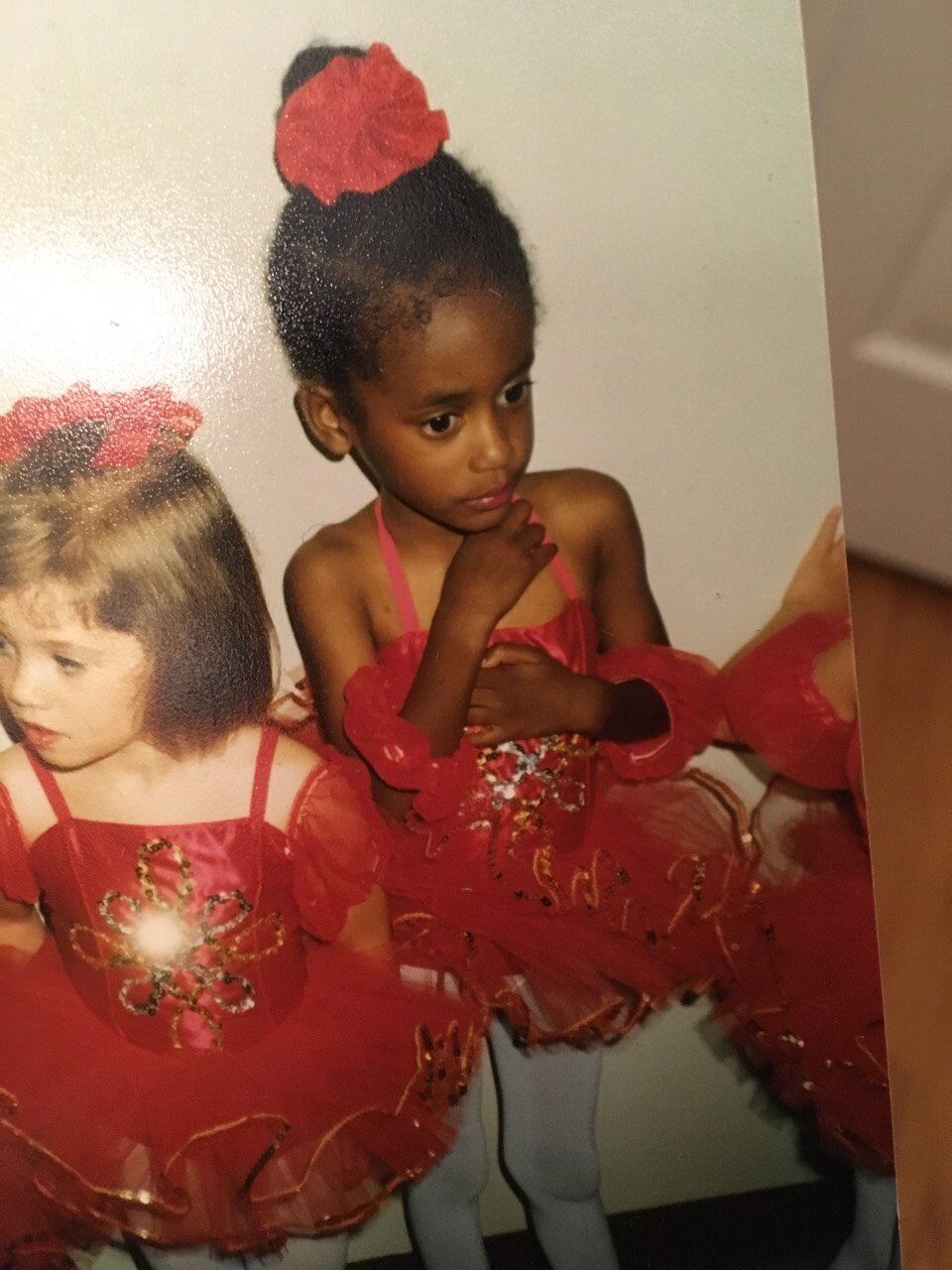

If you had asked me if I wanted to be white, I would have said no, but I definitely didn’t want to be myself either. From a young age, I envied the Black girls on the box of the Just For Me hair relaxers. I had long, thick, coarse hair that my mom braided and straightened with a hot comb for special occasions. But it wouldn’t lie flat. It didn’t fit in a bun either - it poofed! I disliked my braids which my mother would plait and then pin Fräulein Maria style on top of my grade-school head. It didn’t look right. In fact, I didn’t know of any other Black girls with my Sound of Music hairstyle - not even my older sisters. At the very least, I wanted round brightly colored barrettes and evenly spaced cornrows. But more than anything, what I really wanted was long straight hair.

Like many other Black families of the time, my mom braided our hair at night, and we wore silk panty hose “stocking caps” to bed. Usually, she would cut off the ends, but I frequently would ask her to keep them, so I could pretend I had long silky tresses trailing after me while I twirled around in floor-length cotton pajamas. My no-nonsense mother wasn’t about to allow us to relax our hair either - not until we were older - so I made do with the pantyhose wig and my imagination.

Dressing up for Halloween with my brother!

The message society preached - through cartoons, and commercials, toys and books and through my interactions with peers in grade school - was that physical appearance determined self worth. No one ever had to say this to me directly. This unspoken rule was common knowledge, even from a young age. It determined who was popular, who wanted to sit by whom and who was chosen first. It determined who was written up for not sitting quietly and whose naughty behavior was overlooked, who received extra help and who didn’t and who was worth the investment and who wasn’t. If you were dark skinned, fat, disabled, or Black - your place in the hierarchy was a lot lower down. That much was clear.

“To be socially acceptable, you have to be as close as possible to the white ideal of beauty,” my sister explained to me years later. “The whole point of internalized racism is that you don’t have to think about it. You’ve been raised in a society that molds you and shapes you to be a certain way. You never stop to think that it’s unfair.”

We knew as children the “right way” to do our hair. It had to be long and straight and in its natural color. Our hair was long but it broke barrettes and popped hair bands and wouldn’t lie flat. Our hair was unmanageable - or so we thought. In addition to relaxed hair, we also knew that “pretty Black girls” had light skin, of course.

Colorism

I knew from a young age that white, blonde, blue-eyed children wielded the most social capital in the classroom and on the playground. This isn’t something my parents taught me, it’s something I learned at school, and from television and books. On T.V., dark skinned black kids were bullies, lazy, poorly behaved, or just poor. Shows like Fresh Prince (1990), Martin (1992) and later, Proud Family (2001) reinforced this stereotype. And of course, blonde white children were always the heroes, if they were male, or princesses, if they were female. She-Ra (1985) and Voltron (1984) demonstrated that white girls could be princesses and heroines - pushing the envelope of what was possible. Yes, we see you X-Men (1992) and four seasons of Power Rangers, but we raise you damn near every other show and the glaring lack of positive representation for young Black girls in 90s pop culture. Doc McStuffins was still decades away. Also, we didn’t have cable.

My So Called Oreo Life. Have you ever felt lonely in a crowd? That’s what growing up Black in mostly white communities felt like. Photo courtesy of James Stremmel

In my favorite shows and films, Black actors of varying skin colors were invariably paired with light-skinned Black actresses. So I also knew that colorism was gendered. To be considered beautiful, Black women had to have light skin and weave or long chemically straightened hair. The rest of us would be lucky to get ‘exotic’ or ‘‘pretty for a Black girl.’ Dark skin was a disqualifier for beauty - so were African features - a wide nose, big lips, or curves. If you couldn’t be white, you had better be biracial, or multi-racial. And if you couldn’t be that, you should at least look like Halle Berry. Anything else was like you weren’t even trying.

Fortunately, colorism wasn’t enforced at home. With four African American kids, you never knew which white ancestor was going to make a sudden appearance. Our skin tones didn’t exactly match, but they were close. My parents didn’t comment negatively on our skin color. We were free to spend as much time as we could outside and to get as dark as we wanted. So we did. But skin color is something I was always aware of. It didn’t seem to matter as much for guys, but I knew it mattered for girls. Lighter was better. The best was being racially ambiguous or white passing, like the handful of white kids in my public middle school, with Hispanic surnames. That was cool. It made you interesting, while insulating you from anti-Blackness.

However, our parents couldn’t protect us from colorism or featurism which was the norm everywhere else. At the end of sixth grade, I cut all of my hair off. It was a pretty liberating feeling. At an age when I had very little control over anything, this was something I could do: opt out of white beauty standards. But I couldn’t change my face. Starting in middle school, strangers on the street would stop me to tell me that I was beautiful or exotic - something I attribute to my height, yes, but also to the ways in which Eurocentric features are valued and Afrocentric features are devalued. My face is a combination of both. I have a narrow nose and narrow face with high cheekbones. I have a slim build and zero curves. Hello white ancestors.

As I got older, Black boys would flirt with me by asking if I was mixed. My mom had to explain that this question was supposed to be a compliment. In Black culture, then and now, beauty is associated with lighter skin. Equating beauty with proximity to whiteness was a fucking confusing way to flirt. In reality, it was just another form of colorism, or internalized racism - and very common. After a few years, this turned into Black men complimenting my accent and asking me if I was “from an island.” Face palm. I don’t have an accent. Apparently, there is little attractive about being a medium or dark skinned African American woman descended from West African slaves. Duly noted. It was also common to hear people fetishize biracial or multiracial children as beautiful and more attractive than kids with two Black biological parents. Between colorism and losing the “good hair” battle, I was primed for the next symptom of growing up “white”: isolation.

Isolation

Growing up as a Black kid in a mostly white community meant feeling isolated all of the time. I really valued my family, because it was where I felt safe. And my mom was great at using words of affirmation to try to boost our self confidence and sense of self worth. I often shrugged off her remarks though. I told her she didn’t know what she was talking about, or that she only said those things because she was my mom. She talked openly about race and racism and I often accused her of being intolerant for mentioning race so much. Gaslighting your own mother - anyone? Anyone else? No, just me? Okay then.

Outside of my family, I didn’t feel very confident or comfortable. I was in awe of my middle sister who has always navigated her mostly white peers - seemingly without a shred of self-doubt, while I was constantly wondering if I was being judged, or if my discomfort was just in my head. I felt more comfortable being around other Black people, because it made me feel safe - similar to how I felt around my family. However, I was shy, deeply introverted and not that great at reaching out, or making friends. And I ended up feeling even more isolated after I chose to move from my public school to a nearly all white boarding school where girls made comments like, apples and oranges just don’t mix, in reference to Black and white students.

I focused on excelling in academics and sports, which were the perfect outlet for the anger I felt. When I reflect back on the isolation I experienced, I believe that it came from a desire to belong. I felt like I knew the white kids I grew up alongside better than they knew themselves - and certainly better than they knew me. We liked the same music, films, comics, art, sports — the same people! We spoke the same language, but it didn’t make a difference. I saw us as the same. They saw me as other which contributed to a deepening sense of alienation.

I noticed that the Black kids who did a ‘better job’ of being accepted seemed to fill a specific role for white people. They played basketball or football, they were the class clown, the sassy black friend, or they made more effort to conform to white beauty standards. I was none of those things. I wasn’t quick-witted or clever enough to be an entertainer; I wasn’t skilled or disciplined enough to be a serious athlete; and I didn’t have enough sass to be someone’s black best friend. And who would want to? All of those identities were stereotypes. I was quiet and very serious — 6’1” with chocolate brown skin and short hair. I liked science fiction, running, anime and emo music. There didn’t seem to be a place where I could be myself and fit in. Not in popular culture and certainly not in high school.

As I grew older, and was influenced more by my peers (again, mostly white) than by my family, I started to internalize, more and more, a low sense of self worth. I also felt a lot of anger and resentment, although I didn’t exactly know why.

“You Don’t Sound Black”

When we matriculated from our mostly white grade school to a slightly more diverse middle school, my brother, who had played travel soccer for years, suddenly dropped the sport to play basketball. He remembers the transition as a rude awakening.

“As a kid I was extremely embarrassed about not quite fitting in with the white kids, or with the Black kids,” he said. “That’s the first time I understood or felt the stratification of race. Before in elementary school, you go outside, run around and play with anybody.”

Then there was the issue of basketball. Once he reached a certain height and age, everyone asked him if he played basketball - everywhere he went, including total strangers. “It wasn’t until I got older that I realized that I really don’t like it when people ask me that question,” my brother reflected. “It bothers me. Somehow my self worth had been tied to a sport or entertainment for other people.” There was a lot of pressure to fit a certain stereotype.

“No one was like, hey are you into coding? Or poetry? Or engineering?” he added. “Instead, the conversation started and ended with ‘do you play basketball?’ It’s a stereotype. A tall Black man is expected to do something physical, instead of something academic. With Laura Ingraham telling Lebron James to shut up and dribble, I realized there is a much darker undertone to that question. Shut up and entertain me. We don’t expect you to have any other thoughts, ideas, dreams or goals.”

Respectability Politics

In Black families, respectability politics is about shaping your child to be acceptable to White society. Black people are often stereotyped as dirty, so your child must be well-groomed and impeccably dressed. Black hairstyles are derided as unprofessional and unkempt, so your child’s hair must be kept short (for boys) or chemically straightened (for girls). In our family, we weren’t allowed to relax our hair until middle school. But we also didn’t wear extensions, weave, locs or cornrows and we didn’t experiment with different hair color. My brother occasionally grew his afro out during the summer, but always cut it right before school began in the fall. Respectability politics seemed to blame Black people for the racism that we experienced and demand that we prove to whites that we were good enough. It was exhausting. It was also a survival strategy.

Black people are discriminated against for speaking AAVE, so we didn’t in our household. In school, when we were around other Black kids, we were often called Oreos or bullied for ‘talking white.’ They weren’t wrong, but what they didn’t realize was that talking white was endgame. We worked hard at it. My mother worked on our diction incessantly and was serious about giving us the best possible chance of success in a racist society.

Black people are stereotyped as loud, so we were raised to be quiet and polite and to avoid taking up space. We were obedient, respectful, well-disciplined kids - and this was something that other white families in our neighborhood, in our church, and in our community frequently commented on. I didn’t explicitly understand the underlying message until I was older - ‘your family is one of the good ones - not like those other Black people.’

A NYC reunion with college friends in 2011. Photo courtesy of Crystal W.

Like a lot of the internalized racism I acquired in childhood, I later understood that part of it was our parents doing their best to protect us from the bigger dangers of the world, namely racism. Many minorities are wed to the model minority myth — that if we keep our head down and work hard, we’ll be rewarded with success and economic prosperity. This is not true for most, but especially not true for African Americans who experience horrific overt and insidious forms of racial discrimination in the U.S. But plenty of Black people still live by respectability politics, or the idea that bad things happen to bad people, but we are the good ones. And this isn’t a new concept.

When I went to school, sat quietly, and observed other Black girls speaking loudly, laughing loudly, taking up space and drawing attention to themselves, I knew in the back of my mind that I was one of the good ones. Bad things wouldn’t happen to me as long as I played by the rules. I passed judgment. I was also jealous. I wanted to be like them — loud, funny, confident. I wanted other Black girls to like me, but I wasn’t sure how. I’m still amazed by the ones who did. A girl named Francesca made middle school bearable. In high school, a wise beyond her years underclassman named Rumbidzai introduced me to Sylvia Plath, Buffy and feminism. It wasn’t until college that I had the courage to approach other Black women and introduce myself, or to be myself: shy, awkward, funny.

The goal of every Black parent, in pushing respectability politics, was to make it easier for us to move through the world, to be successful, to be accepted, to experience less harmful forms of racism - none of this worked out - but it was lined with good intentions.

“Twice As Good For Half As Much”

When I was younger, my mother frequently explained that as Black children living in a racist society, we would need to be twice as good as our white peers in order to attain half as much. She pushed us to excel in school, and disciplined us if we brought home grades that were below our capability. I got mostly straight As, and worked hard at track, cross country and rowing. Twice as good for half as much is the other side of respectability politics. It’s the realization that being polite, respectful, well groomed, well spoken and Black isn’t enough and won’t ensure that you are treated equally by society. It’s every reminder your parents give that if you act up with your little (White) friends, their parents will be able to get them out of trouble, but yours won’t. So you had better stay out of trouble.

Post Racial America

High school formal my senior year in 2004.

I was also a product of a formal education that reinforced that racism was a thing of the past. White teachers, textbooks, and authority figures explained that the much beloved Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had fixed it all, shortly before being assassinated, right? In the 90s, a U.S. public education included a lot of post-racial myth building. No, the concept of post-racial America didn’t start with President Obama’s inauguration in 2009. The term dates back to Durham NC and 1971 and it was a tremendous source of gaslighting during my childhood — much of it self-inflicted. How could I be experiencing racism if it no longer existed.

The belief that America had transcended racial prejudice pervaded my childhood - if not my home. In school, we weren’t taught about the different types of present day discrimination that Black people face. Racism was always framed as a thing of the past.

Thus, when I was called a nigger twice in grade school or when my mom resorted to carrying my brother’s birth certificate to soccer games after white mothers insisted, multiple times, that he was “too old” to play with their children, it never occurred to me to think of racism as more than a few outliers perpetuating misguided and outdated beliefs. I continued to think of racism in terms of bad people, instead of bad systems designed to keep power and privilege consolidated within one racial demographic.

None of those experiences felt post-racial. But they were easier to comprehend and process than the more subtle discrimination of being excluded, of being called exotic or pretty for a black girl, of never being in a room where everyone else looked like you, of rarely having teachers who looked like you, of feeling criminalized, dehumanized and un-desirable or alone for reasons that included being born Black in America.

As knowledge of the outdoors tends to be handed down generationally, this broken chain has denied today’s black youth the tools they need to be able to tackle the outdoors with any degree of confidence […] we have effectively become an urbanised people.