4 Pieces of U.S. History You Weren't Taught In School

Entrance sign for Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. Photo credit: Chris Light (Wikimedia Commons)

There’s been a lot in the news lately about the right-wing backlash to “Critical Race Theory—a term coined by legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw—which examines how historical biases help perpetuate institutionalized racism.

Yet the term has since been taken up by the right-wing media as a catch-all for anything designed to teach students about the discrimination that Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) face in this country.

Efforts to erase BIPOC history aren’t new; they’re just getting more media attention. Here are four historical events that we should never forget—and that you most likely never learned about in school.

1. Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

Depiction of the Sand Creek Massacre by Cheyenne eyewitness and artist Howling Wolf. Photo credit: Howling Wolf

Have you heard of the Sand Creek massacre? On the morning of November 29, 1864, U.S. Army troops attacked a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho sheltering at Sand Creek. The soldiers murdered over 230 people, including about 150 women, children, and elderly.

It’s considered one of the most violent attacks on any indigenous nation in American history. It was so violent that public backlash prompted the US government to issue a formal apology to the Cheyenne and Arapaho along with the promise of land reparations and cash.

So what led up to it? Before 1850, there were few American settlements in Colorado. However, in 1859, the discovery of gold led to rapid population growth, increasing pressure on the US government to step up ethnic cleansing efforts in the territory.

In 1864, Colorado Governor John Evans even issued a legal decree allowing settlers to “kill and destroy” all Indigenous people considered “hostile” (Gov. John Evans). The decree wasn’t officially repealed until 2021.

Manifest destiny was also national policy. A few years earlier in 1862, the US government had passed the Homestead Act—reallocating land seized from indigenous tribes to White settlers for low cost—and the Pacific Railway Act, which gave Congress the power to seize “[Native American] titles to all lands falling under the operation of this act”.

Almost 160 years later, the descendants of the Sand Creek survivors still seek justice for the event. The reparations offered by the US government were empty promises. The legacy of the massacre also lives on in other painful ways. Despite being forced to resign, Governor Evans is still honored today for founding Northwestern University and the University of Denver.

Violence against Native people persists to this day—especially in parts of the U.S. that are tied to extraction industries (e.g. - logging, uranium, natural gas).

As of 2023, 3.5% of all officially registered missing persons in the United States were identified as Native American and Alaska Native even though they make up just 1.1% of the population. That same year, murder was officially cited as the third leading cause of death for the same demographic. Native women are three times more likely to be murdered than white women, and two times more likely to be sexually assaulted.

It’s more important than ever to educate ourselves on the violent settler-colonial origins of America. Only then will we be able to push for policies that protect future generations of Indigenous people from harm.

2. Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek (1887)

Chinese Gold Miners in Idaho Springs, Idaho 1920. Photo credit: Dr. James Underhill

The massacre at Deep Creek in Idaho took place only 23 years after the Sand Creek massacre—and gold also played a role. On May 27, 1887, a gang of horse thieves gunned down more than 30 Chinese gold miners on the Snake River in Hells Canyon. The murders weren’t discovered until the bodies of the 30 miners were found by locals miles downstream. The company the men were associated with, the Sam Yup Company of San Francisco, had to hire a local investigator to figure out exactly what happened.

At the time there was a lot of resentment towards Chinese immigrants who were blamed for the decline of railroad and mining jobs and for “taking jobs away from White workers”. According to historian and author Marie Rose Wong, cited by Oregon Public Broadcasting:

“The Chinese were looked at as scapegoats. They were really blamed for any kind of economic downfall that was taking place in the United States. You see the Chinese being chased out.”

By the time the miners were lynched, tensions were already high between Chinese laborers and white settlers—enabled by 1882 U.S. legislation that banned new immigration from China and denied citizenship to Chinese already living in the U.S. Two years before the Deep Creek massacre, 28 Chinese miners were murdered in Rock Springs, Wyoming. A year before, in February 1886, a white working class mob violently expelled Seattle’s entire Chinese population. By November 1886, Tacoma’s Chinatown was also empty. Anti-Chinese hatred was spreading like wildfire across the Pacific Northwest—fueled by economic anxieties and racism.

It took a year for the murderers to come forward and when they did, they were never held accountable for the crime.

The site where the men were murdered remains relatively untouched. Many remnants of the original campsite still remain. The incident is unfortunately one of many unprovoked, racially motivated attacks on a group of people who were perceived to be ‘inferior’ but also as ‘competition’. Anti-Chinese racism isn’t new to the U.S.

We weren’t taught this in school because it doesn’t fit the neatly packaged narrative of the U.S. as a welcoming, multicultural society. The men deliberately chose a remote camp to keep a low profile and avoid white mob violence. They were killed anyways and their families never received justice.

The Deep Creek massacre reminds us of our country’s long history of violence against Asian communities. We can’t move forward without acknowledging our past.

3. Johnson-Jeffries Race Massacre (1910)

Jack Johnson vs James Jefferies July 4, 1910

On July 4, 1910, world heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson was scheduled to face off against former world heavyweight champion James Jeffries. The highly anticipated 1910 Johnson-Jeffries match was heralded as “the fight of the century.”

Johnson, the current world title holder, was good-looking, charismatic and—worst of all, seemed not to ‘know his place’ as a Black man in Jim Crow America. The “son of emancipated slaves” defied conventions, publicly dated white women, and “defeated whites in the ring”.

On the other hand, his opponent Jeffries had retired five years earlier “because no white man was left to fight him.” After years of refusing Johnson’s challenges, “The Great White Hope” returned to the ring to demonstrate the ‘superiority of the white race’.

A New York Times editorial spoke for many when it said:

“If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than physical equality with their white neighbors”.

Johnson won.

Black supporters poured into the streets in celebration—a move which angered whites. In New York, white lynch mobs roamed Black neighborhoods setting fires to tenement houses and blocking exits. They also assaulted anyone they could get their hands on, killing one man and injuring over 100 others. The attackers sustained injuries as their victims fought back.

This pattern repeated itself in major cities and even in small towns across the U.S. In Norfolk Virginia, hundreds of white Navy sailors hunted Black people for sport. In Uvalda, Georgia, whites fired into a housing area for Black construction workers, killing several. In Wheeling, West Virginia, a Black man driving an expensive car was seized and hanged. In Houston, a Black man had his throat cut for celebrating Johnson’s victory on a street car. A total of 26 were killed and hundreds were injured—almost all African American.

The Johnson-Jeffries race massacre was another reminder that Black people could be killed for being too successful, or for ‘not knowing their place’ in the country’s rigid racial caste system. The lynchings formed an unbroken line of racial terrorism that includes massacres in New York (1863), Opelousas (1868), Vicksburg (1874), Clinton (1875), Thibodaux (1887), Slocum (1910) Chicago and Elaine (1919), Ocoee (1920), Tulsa (1921), Rosewood (1923) and Philadelphia (1985). The Johnson-Jeffries lynchings are a reminder that Black people in America are only allowed so much joy, only so much success.

4. Zoot Suit Mob Violence (1943)

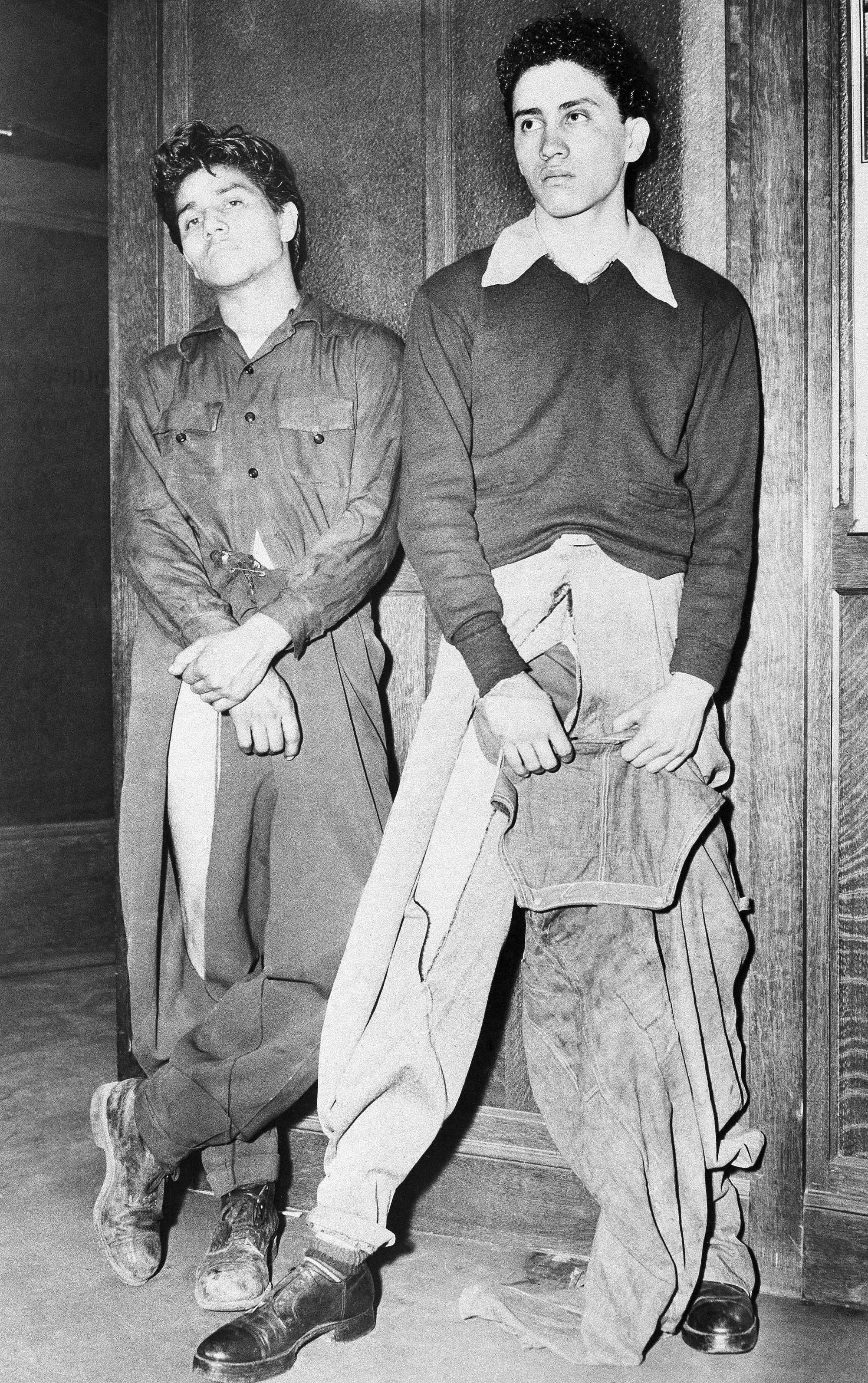

Noe Vasquez, left, 18, and Joe Vasquez, 18, unrelated to Noe, reported to Los Angeles, Calif., police they were seized by sailors who tore peg-topped trousers, although one youths wore overalls over them, June 12, 1943. Photo credit: Associated Press (public domain)

As the United States was fighting fascism abroad, racially motivated violence broke out in Los Angeles. Mobs of U.S. Navy sailors roamed the streets assaulting Mexican-American teens.

On the surface, tensions swirled around the zoot suit itself. Labeled by whites as a “badge of delinquency”, the stylish slouchy trousers, long jackets, and fedoras originated in Harlem before being adopted by Black, Mexican, and Filipino Angelenos.

Beneath the surface, the violence was, of course, racially motivated. White servicemembers and police officers dehumanized Latines as violent criminals and draft dodgers—despite their record of military service—and “the local media was only too happy to fan the flames of racism and moral outrage”. In the minds of many, these racial stereotypes justified white mob violence.

On June 3rd, 1943, a bar fight between white sailors and Latine youth provided the spark—however it’s important to remember, as Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in a column for the New York Times, the violence was really a result of “long-standing discrimination against the Mexicans in the Southwest.”

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, whites in uniform spent five days storming the streets, stripping young Chicanos of their clothing and burning their suits, dragging “zoot-suiters” out of bars, and cafes, and attacking them in movie theaters.

The assaults expanded to include Blacks and Filipinos. Instead of halting the violence, the LAPD participated or watched from the sidelines. In many cases, they waited until the white sailors left before arresting the victims.

Mexican American community leaders asked city and state officials to intervene. They even sent a telegram to President Roosevelt. However, the violence continued unchecked until June 8 when the U.S. military issued an order restricting servicemembers to their barracks. In the aftermath, the media was quick to frame the attacks as a necessary “vigilante response to an immigrant crime wave”. The City Council banned zoot suits from being worn.

It’s not hard to draw parallels between what is happening in American politics today and the legacy of these events - whether it is election year fear mongering around so-called “migrant crime waves’, the scapegoating of Asian Americans, the ongoing Missing, Murdered Indigenous Person (MMIP) crisis, or the country’s refusal to face its anti-Black racism.

When politicians ban the teaching of BIPOC history in schools, they are desperately attempting to manufacture a version of the U.S. that does not exist. It’s Manifest Destiny all over again. It’s impossible to maintain the illusion that white supremacy is “natural” in a land that has always been multicultural and Indigenous.

In order to fulfill the empty promises of democracy, we need to be very clear-eyed about the ways this country has failed to live up to its own professed ideals. Teaching younger generations about this country’s difficult history in schools will not only empower marginalized youth, it will ultimately help everyone make better political decisions - about everything from immigration policy to climate change - going forward.

That starts with us. Know your history—even the difficult parts.

Sources:

Janel George. “A Lesson on Critical Race Theory”. American Bar Association, January 11, 2021.

Eric Gorski. “Sand Creek Massacre Descendants Seek Justice 148 Years Later”. The Denver Post, December 29, 2012.

Savannah Maher. “Supreme Court Rules Tribal Police Can Detain Non-Natives, But Problems Remain”. NPR, June 9, 2021.

Billy J. Stratton. “The Sand Creek Massacre Took Place More Than 150 Years Ago. It Still Matters”. Time Magazine, November 29, 2016.

Native Hope. “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW): Across the United States and Canada Native Women and Girls are Being Taken and Murdered at an Unrelenting Rate”, https://www.nativehope.org/missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-mmiw.

A.Skylar Joseph. “A Modern Trail of Tears: The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) Crisis in the US”. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Vol. 79 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2021.102136

Kami Horton. “Remembering the 1887 Massacre at Hells Canyon”. Oregon Public Broadcasting, May 27, 2023.

Michael Walsh. “A Year of Hope for Joplin and Johnson”. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2010.

Library of Congress. “A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil RIghts Cases and Events in the United States: 1942 People v. Zamora; 1943: Zoot Suit Riots”, https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/people-v-zamorra

Jack Johnson vs. James Jeffries: Topics in Chronicling America”, https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-johnson-vs-jeffries

Southern Poverty Law Center. “The Zoot Suit Riots”, originally published in Us and Them: A History of Intolerance in America in 2006, https://www.learningforjustice.org/classroom-resources/texts/the-zootsuit-riots

Further Reading

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States.

Ibram X. Kendi. Stamped From the Beginning.

Geoffrey C. Ward. Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson.

Mauricio Mazon. The Zoot Suit Riots: The Psychology of Symbolic Annihilation.

R. Gregory Nokes. Massacred for Gold.

Marie Rose Wong, PhD. Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon.

Image Sources:

Sand Creek Buffalo Skin Drawing:

Depiction of the Sand Creek Massacre by Cheyenne eyewitness and artist Howling Wolf

Dr. James Underhill poses with Chinese-American miners (probably) in the Colorado School of Mines' Edgar Experimental Mine near Idaho Springs (Clear Creek County), Colorado. One man holds a saw.

Jack Johnson vs. James Jeffries:

Jeffries knock-out from the 1910 prize-fight

Two Victims of Assault by U.S. Servicemen

Noe Vasquez, left, 18, and Joe Vasquez, 18, unrelated to Noe, reported to Los Angeles, Calif., police they were seized by sailors who tore peg-topped trousers, although one youths wore overalls over them, June 12, 1943.

“[Reclaiming food sovereignty] has to be inter-generational work,” Antonio concluded. “It has to be beautiful, fun, sexy, and fulfilling—and [it] takes good people and good organizing.”