Finding My Identity as a Chinese Adoptee

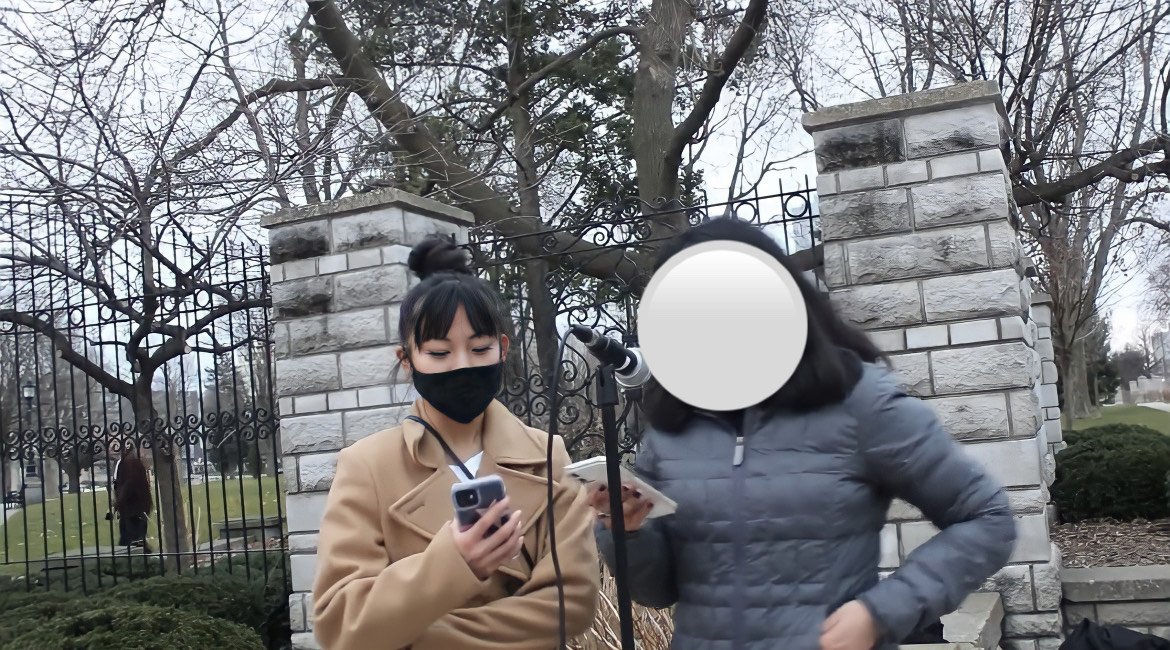

Photo courtesy of author

Twenty three years ago, I was adopted from China by a white Canadian couple. This isn’t an uncommon experience; couples in the West adopting babies from Asian countries was like a fad around the 2000s. As a result, a bunch of us transnational and transracial adoptees grew up in a completely different country, continent, and culture than we would have otherwise.

I was raised in Ontario, Canada. The city I grew up in was predominantly white, especially during my childhood. My parents were white, my teachers were white, my friends and classmates were white, and I didn’t really understand that I wasn’t. As a young child, I had no idea that I was a different race from my adoptive parents. My mom, a natural blond, would try to explain to me that my hair was black, and I would insist that, no, my hair was just “dark blond.” I knew that I had been born in China, but I couldn’t grasp that I was Chinese.

When I really began to understand that I looked different from others, it was because classmates would point it out to me, or adults would ask my parents questions about me. My growing realization that I was not the same race as my parents or as most of those around me was a negative one, and all I wanted to do was draw as little attention to it as possible. I didn’t want to learn Mandarin, learn about China, talk about China, or admit that I was Chinese. Why would I want to invite others to mock my eyes, my language, culture, skin tone, or appearance? Boys made it clear that white girls were the most attractive; my peers made it clear that Chinese culture was weird and our food was gross.

I started high school with the mindset that I should aim to make friends with lots of white people, and ensure I was never seen with too many other Asians. Having Asian friends was uncool, and only invited negative attention. Among racialized folks, high schools in Ontario have a reputation for being some of the most hostile, overtly racist environments you could find yourself in. My high school was no exception.

“I hadn’t been raised by Asian parents, I had never been taught to speak Mandarin, I didn’t know how to make Chinese food, and I had no real connection to my homeland.”

That time of my life wasn’t all bad, though; around grade 11, I began to befriend and hang out with other racialized people from diverse cultural backgrounds. These people showed me that it was okay to embrace differences in race, ethnicity, and culture. They were proud of and connected to their heritages, and spoke openly about racism they experienced. This drastically challenged my own views on race. It was the beginning of me realizing that I had been spent so much energy trying to appeal to white people while overlooking the racism that was causing my insecurities. While I still felt shame surrounding my ethnicity, I opened myself up to embracing my race. I was still acutely aware of how intense anti-Chinese racism (or Sinophobia) was in society, but I thought if I continued to distance myself from my Chinese-ness specifically, I could at least embrace my Asian-ness.

What I learned at this time was that embracing my race was not going to be easy, and in part because people loved to invalidate my Asian identity. I hadn’t been raised by Asian parents, I had never been taught to speak Mandarin, I didn’t know how to make Chinese food, and I had no real connection to my homeland. People of all races liked to tell me that I was basically a white person. For the first time, I wasn’t seeing these comments as compliments. I was recognizing them as being invalidating, disrespectful, and untrue.

Despite this slow progress I was making, it was not until the pandemic in 2020 that I took the time to undo some of my internalized Sinophobia and shame. Perhaps it was because of the increase of overt Sinophobia in response to COVID-19 that I was able to acknowledge the complex emotions and thoughts I had been carrying throughout my life. I also, for the first time, was introduced to other Chinese and Asian people my age who were actively engaging in anti-racism work over social media.

I learned about the vast history of anti-Chinese sentiment that Canada and the United States was built on, about how Western imperialism and anti-Asian racism go hand-in-hand, about the faults of the model minority myth, and about the unethical practices of the adoption industry from an anti-racism lens. I decided I wanted to take action with all of this information I had learned, and began to speak out against Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism. I posted videos breaking down key concepts; I organized a vigil and rally after the 2021 tragic shooting of Asian American women in Atlanta; I spoke at panels and put together infographics; and took any opportunity I could find to educate people on anti-Asian racism. I felt like I was finally finding my place in the world.

And yet, people still found ways to invalidate me and weaponize my adoption against me. Those comments about me being ‘white on the inside’ didn’t go away. It didn’t matter that I am Chinese, or that I experience anti-Asian and anti-Chinese racism, or that I was spending my time and energy advocating for the Asian community. Some people could still only see me as whitewashed, and not fully Asian.

Photo courtesy of author

I began to wonder: what makes someone Asian? What makes someone Chinese? Why do those who continue to reject their cultures while refusing to stand up for their communities still get a claim to Asian-ness, but I don’t? People act like drinking bubble tea is what makes them Asian. And this was when I learned the term “boba liberalism.”

“Boba liberal” is a term used to describe someone from the East or Southeast Asian diaspora, usually middle or upper class, who primarily connects with their Asian-ness through surface level activities and traits (like drinking bubble tea/boba) while touting capitalist ideology and adhering to the model minority myth. They look to gain a closeness to whiteness while tokenizing themselves as Asians. They might talk nonstop about Asian representation and post #StopAsianHate because it benefits them, but when it comes to discrimination against other racialized non-Asian groups, they remain silent. At the end of the day, they only care about anti-racism and social justice as long as it doesn’t threaten the status quo.They might care about a Crazy Rich Asians poster being vandalized, but they don’t care about the amount of Chinese elders living in poverty in Chinatowns. While a lot of people use the term boba liberalism incorrectly to describe Asian leftists, it was always meant to criticize liberal Asians who assimilate or dissolve into whiteness and abandon their communities.

Photo courtesy of author

Learning about this term helped me re-evaluate my own identity and relationship to Asian-ness, and even gave me insight into how my experience with adoption–being taken unwillingly from my homeland; experiencing racism, racial fetishization, Sinophobia, and racialized misogyny; losing access to my language and culture, and then still being questioned and invalidated by others–-is an incredibly Asian experience. This term, and the analysis that comes with it, gave a whole new meaning to what it means to be whitewashed.

I was constantly told that I was whitewashed by my adoptive parents, friends, strangers, and even an ex of mine. I grappled with it for so long. Even as I began to take pride in my Chinese heritage, I immediately was made to feel like I couldn’t call myself Chinese. But now, I have been given the tools and terminology to see whitewashing not as simply lacking fluency in your mother tongue, but as turning your back on community; rejecting collectivism for individualism; and actively appealing to whiteness. It isn’t somebody’s fault that they weren’t taught Mandarin growing up, or that they were adopted by white parents, and it doesn’t make that person any less Asian. What makes you less Asian is turning your back on your people and their history and throwing your own community under the bus if it means you can climb the ladder.

This isn’t to say my struggle as an adoptee is resolved. The damage of being separated from my homeland and culture can never be fully undone. I still spend energy convincing others that I have a right to claim my Chinese and Asian identity, and to see my struggle as an adoptee as legitimate. But I have gained more of a community based on shared values and goals than I think I would have had access to had I boxed myself in and tried to be what others thought I should be. I have gained confidence in who I am; pride in my heritage and in my ancestors despite not knowing my specific family line; and a passion to advocate for others in similar situations.

Esther Park is on a mission to help women in skydiving fit in–literally.

She left a comfortable job in scientific sales after a life-changing skydiving accident. Since then, she founded a company, Girls in Sky Places, to help women find correctly-sized gear.